What is TLS?

TLS, or Transport Layer Security, is an encryption and authentication protocol that’s designed to keep your data safe when browsing. It’s the S in HTTPS, FTPS, and one of the S-es in SMTPS. It’s what allows the padlock in the browser to padlock. The TLS protocol natively works with anything that runs on the TCP protocol. This is why you see TLS all over the place!

A TLS session is established right after the TCP connection is established, and before any application-protocol level (Read, HTTP, FTP, etc) shenanigans start. This ensures that anything that happens in the application layer is automatically encrypted from the beginning. This session establishment happens with a process called a TLS Handshake.

We won’t delve too deep into TLS settings itself. Instead, the rest of this post will go through the TLS handshake, and try to simulate it manually using OpenSSL, so we can get a feel of what it actually does. I hope you find this helpful!

Aside:

I will be using RSA throughout this article to refer to the concept of asymmetric-key based encryption protocols in general, and AES to refer to the concept of symmetric key based encryption protocols. Is is 100% possible to switch out both these in TLS. You can even use a different key exchange algorithm. For example, you can use tls_ecdhe_ecdsa_with_chacha20_poly1305_sha256 - which uses the Elliptic Curve Diffie Hellman key exchange (ecdhe) instead of RSA or standard DH , with the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ecdsa) instead of RSA, and ChaCha20-Poly1305 (chacha20_poly1305) instead of AES.

Side Quest: Why do we need to make an AES based tunnel?

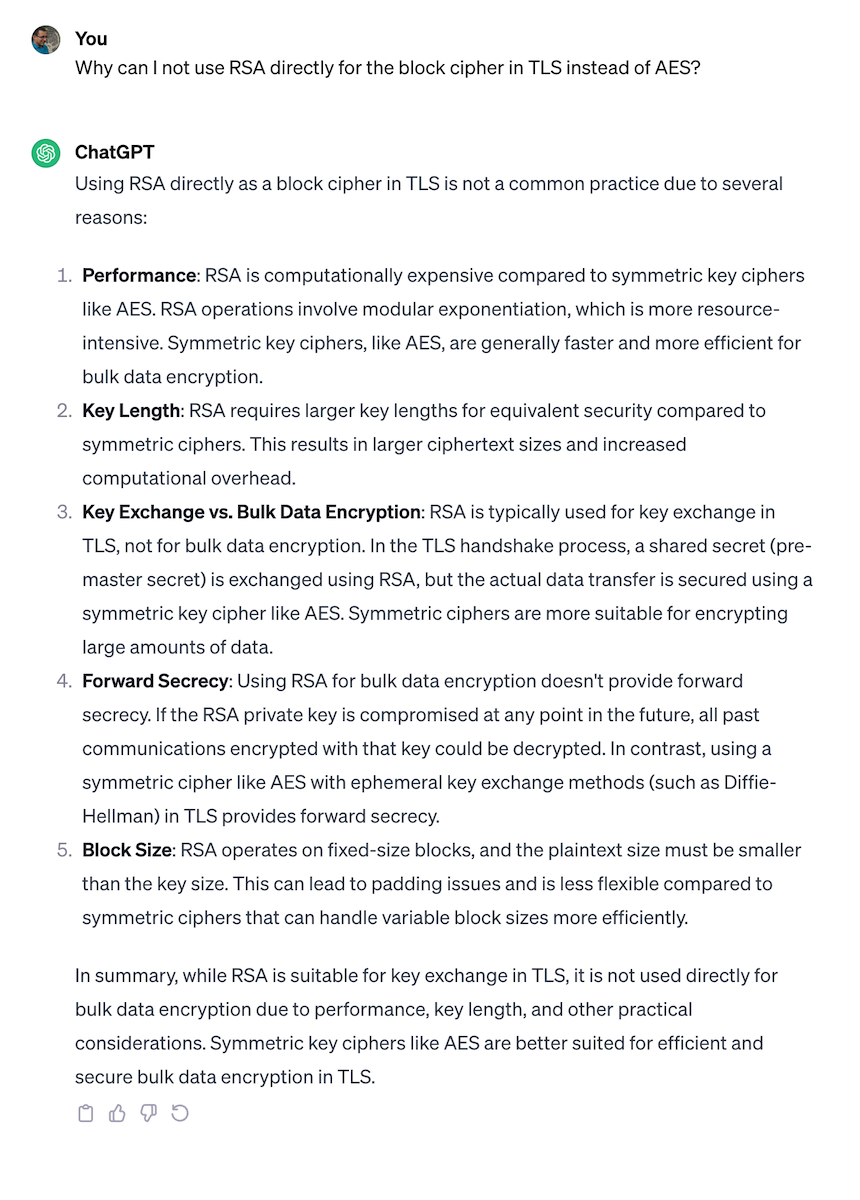

If you wonder why TLS uses RSA for digital signatures, but then uses that to make an AES based tunnel instead of just using the RSA algorithm itself for the tunnel, you’re not alone!

A cursory browse of this question may lead you to believe that it’s because RSA is slower, meant to be used on fixed or small sizes of data, or that it adds unnecessary overhead. If you drill a bit deeper into RSA vs AES, you may even find that using RSA in block cipher mode is nebulously “insecure.” Scary! Even if we ask our lord and saviour ChatGPT, it answers thusly:

But Beware! All is not as it seems!

The simplest reason why you can’t use RSA to encrypt the connection directly is straightforward, almost annoyingly so: RSA is asymmetric, so you can only encrypt data from the client to the server! Anything the server sends back to the client will be public knowledge. Not exactly secure now, is it?

The asymmetric part of TLS is not for encryption, but for the client to verify that it is actually talking to the correct server. For example, the Diffie Hellman key exchange does not rely on a private channel to create the shared symmetric key. You can perform DH by literally shouting out the values to each other, and no one else will be able to “break” or listen in to your secrets. When you’re shouting, however, you can see the person shouting back, you can listen to the intonation of their voice, and confirm that it is the person you actually want to talk with. The RSA in TLS ensures the same thing.

In theory, though, you could construct a Mutual-TLS connection, where the client and server authenticate with each other using an extension of the below TLS handshake. In this case, the server can use the client public key to encrypt messages to the client, and the client can use the server certificates to encrypt data to the client. Why do we not do this? The simplest reason is that mTLS is usually not used between clients and servers, as setting up mTLS requires a lot of work on the client end. When it is used, it’s usually used between services within a company, or to authenticate clients between companies where high-trust and security are needed. Wait a second… Communications between services within a company can be much more complex and numerous than between end clients and the server, so we probably want to increase the performance by using faster algorithms and algoritms that have smaller keys. Also, if we want high security, we would probably like to have Forward Secrecy by having transient secrets. Looks like ChatGPT was thinking a couple steps ahead on this one!

In my mind, simply knowing that TLS uses AES for encryption due to performance, forward secrecy, etc isn’t good enough. The road that tells you how you get to that point is equally important!

Setting up the Lab Environment

The lab environment is pretty simple for now:

- A folder each for the certificate authority, the server, and the client

- OpenSSL CLI installed

bash/zshenvironment

Some conventions I will follow are:

- Whenever a

#Labcodeblock is reached, the assumption is that you are starting at the root of the lab. - Files that end in

.pemare public - Files that end in

.keyare private - Files that end in

.binare binary, and are also private

We also set up a few bash functions to make things clearer moving forward. Please note that variables defined in one block of the lab may be used in other blocks as well! Feel free to set this up within a Docker container, if you need to.

# Lab

mkdir ca server client

# Function definitions

# Feel free to analyse these if you want,

# but their implementations aren't too relevant

# converts a number to a hexadecimal representation

# num_to_hex $number $number_of_bytes

function num_to_hex {

printf "%0.$(( 2 * $2 ))x" "$1"

}

# counts the number of bytes in a hex string

function hexstrlen {

echo $(( $(echo "$1" | wc -c | tr -d ' ') / 2 ))

}

# formats a variable size hex string

# a variable size data structure has the first two bytes describing the length of the data

# followed by the data itself

function format_variable_size_hex_str {

echo "$(num_to_hex $(hexstrlen $1) 2)$1"

}

# converts a hex string to bytes

function hex_to_bytes {

echo -n "$1" | xxd -r -p

}

# converts bytes from a file to a hex string

function bytes_file_to_hex {

cat $1 | od -A n -t x1 | sed 's/ *//g' | tr -d '\n'

}

# converts bytes from a file to a hex string

# bytes_file_block_to_hex $file $offset_bytes $block_size_bytes

function bytes_file_block_to_hex {

cat $1 | od -A n -t x1 -j $2 -N $3 | sed 's/ *//g' | tr -d '\n'

}

# converts str to a hex string

function str_to_hex {

echo -n "$1" | od -A n -t x1 | sed 's/ *//g' | tr -d '\n'

}

# function repeat a string a given number of times

# repeat_times $str $times

function repeat_times {

printf "$1%.0s" {1..$2}

}

The TLS Workflow

Prelude: Setting Up The Server

Before a client connects to the server, we need to actually set up the server! Now, our server is pretty magical, in that it will be driven by shell commands, such as cp to send data from the server to the client. Since we’re talking about TLS though, we do need to generate a certificate and get it signed by a CA.

The Certificate Authority

Generating the CA is pretty simple - we just make a private key and certificate pair.

# Lab, CA

cd ca

# Generate the private key for the CA

openssl genrsa -out ca.key 2048

# Generate the CA certificate

openssl req -x509 -new -nodes -key ca.key -sha256 -days 1825 -out cacert.pem

Generating a server certificate

The server needs to generate its own private key, and get it signed by the CA. To do this, it generates a Certificate Signing Request (CSR) and some extension data with (importantly) the digitalSignature attribute, some extra subject names (SANs), etc, and sends it to the CA. The CA verifies that the server is legit, that it does indeed control the DNSes that the server says it owns, and generates a signed certificate for the server and sends it back.

# Lab

# Server

cd server

# Generate the private key

openssl genrsa -out server.key 2048

# generate a Certificate Signing Request (CSR)

openssl req -new -key server.key -out csr.pem -sha256

# generate extension file using HEREDOC

cat > extension.txt <<EOF

authorityKeyIdentifier=keyid,issuer

keyUsage = digitalSignature, nonRepudiation, keyEncipherment, dataEncipherment

subjectAltName = @sans

[sans]

DNS.1 = vaishnavsm.com

DNS.2 = www.vaishnavsm.com

DNS.3 = *.vaishnavsm.com

EOF

# send the CSR to the CA

cp csr.pem extension.txt ../ca/

# ------------

# CA

cd ../ca

# view the CSR and verify that everything is ok

openssl req -text -noout -verify -in csr.pem

# Create signed certificate

openssl x509 -req -in csr.pem -CA cacert.pem -CAkey ca.key -CAcreateserial -out cert.pem -days 825 -sha256 -extfile extension.txt

# View certificate

openssl x509 -text -noout -in cert.pem

# Send certificate back to server

cp cert.pem ../server

Creating The Connection

The TLS (1.2) Handshake

The TLS handshake is the process through which two parties negotiate the encrypted TLS tunnel. It goes:

1. Client Hello

The client sends a message to the server, indicating that it wants to establish the TLS connection. This includes:

- Information about the highest TLS version the client supports (

client_version). - The current GMT UNIX timestamp (

gmt_unix_time) - 28 cryptographically random bytes (

random_bytes). I usedopenssl rand -hex 28to generate the random bytes. - The session id, if a previous session id is to be continued (

session_id). This is empty as we want to negotiate a new connection - The cipher suites that the client supports (

cipher_suites). We specify{ 0x00,0x6B }, which is the code forTLS_DHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA256 - The compression methods to use (

compression_methods). We specify0, which is theNULLcompression method.

# Client to Server:

msg_type: ClientHello

length: <message size>

body:

client_version: { major: 3, minor: 3 }

random: { gmt_unix_time: 1705212000, random_bytes: [ b05595ec06fa079fb2ef7b618b7cdf7fb8234b5a411c505d6f5c30e6 ] }

session_id: <empty>

cipher_suites: { 0x00,0x6B }

compression_methods: 0

# Lab, Client

# We just set up the values of the randoms here - This will be used in the future

# Note that there are a total of 32 bytes in the random:

# 4 from the timestamp and 28 from the random data

CLIENT_TS=1705212000

CLIENT_RANDOM=b05595ec06fa079fb2ef7b618b7cdf7fb8234b5a411c505d6f5c30e6

FULL_CLIENT_RANDOM="$(num_to_hex $CLIENT_TS 4)$CLIENT_RANDOM"

Aside:

Why is the version { major: 3, minor: 3 } if we are talking about TLS 1.2?

TLS 1.0 was considered a minor revision of SSL 3.0 (which was major: 3, minor: 0).

So, TLS 1.0 is major: 3, minor: 1, and the count continues from there.

2. Server Hello

The server responds with its own hello, making choices from the options the client has provided:

server_versioncontains the highest TLS version compatible by both the client and the serverrandomcontains the servers own set of random bytes and timestamp. I usedopenssl rand -hex 28to generate the random bytes.session_idis empty, telling the client that the session will not be cached. TLS session caching is a topic for another time.cipher_suitecontains the cipher suite that has been selected. Since the client only gave one option, and it’s an option the server supports, it selects this and sends it back.compression_methodcontains the compression method selected.

# Server to Client

msg_type: ServerHello

length: <message size>

body:

server_version: { major: 3, minor: 3 }

random: { gmt_unix_time: 1705212010, random_bytes: [ c80d5017a2edec7f8d7daf0aa4b1860b58fff7dbfc3ba004c66a314e ] }

session_id: <empty>

cipher_suite: { 0x00,0x6B }

compression_method: 0

# Lab, Server

# We just set up the values of the randoms here - This will be used in the future

# Note that there are a total of 32 bytes in the random:

# 4 from the timestamp and 28 from the random data

SERVER_TS=1705212010

SERVER_RANDOM=c80d5017a2edec7f8d7daf0aa4b1860b58fff7dbfc3ba004c66a314e

FULL_SERVER_RANDOM="$(num_to_hex $SERVER_TS 4)$SERVER_RANDOM"

3. Server Certificate

Immediately after the Server Hello, the server sends its certificate to the client.

The certificate is sent as an x.509v3 certificate. We simulate this in the lab using cp.

# Server to Client

msg_type: Certificate

length: <message length>

body:

certificate_list: <certificate chain obtained after signing>

# Lab Action

# This is the data sent via `certificate_list` above

cp server/cert.pem client/cert.pem

4. Server Key Exchange Message

Since Diffie Hellman Ephemeral (DHE) requires parameters to be sent over what is in the certificate, the server sends this next.

In the lab, we generate the DHE parameters using openssl, as shown below. The server generates both the public prime and generator values for DH, and also its own private prime and the corresponding public key using the generated prime and generator.

The message also includes a signed hash. This signed hash is what prevents an attacker from simply serving you the (public) certificate of the server and pretending to be the server, as it’s impossible to digitally sign data without the private key. Note that until this step, nothing has been digitally signed by the server! This will occur at different points during the key exchange step, but the server will either send some digitally signed data to the client, or the client will send some encrypted data to the server to prevent this attack. The signed value contains the full random sent by both the client and server in the corresponding Hellos (32 bytes = 4 byte timestamp + 28 random bytes each), appended with the bytes in the params struct. The random bytes prevent replay attacks. Note that the params struct has variable sized values for the DH parameters, so the data sent to the hash will be random bytes + size of dh_p (2 bytes) + raw bytes of dh_p + size of dh_g (2 bytes) + raw bytes of dh_g + size of dh_Ys + raw bytes of dh_Ys.

# Lab, Server

cd server

# this can take some time!

# this is usually done in advance, in most real world scenarios

openssl dhparam -out dhparam.pem 2048

# view the parameters

# these are the prime and generator values,

# which will be common between the server and client

# and the server sends this to the client to use

openssl dhparam -in dhparam.pem -text -noout

# generate the private key for the server

openssl genpkey -paramfile dhparam.pem -out dhserver.key

# get the public (g^(Ys) mod P, with g and P as given above) value for the server

openssl pkey -in dhserver.key -pubout -out dhserver.pem

# view the parameters

openssl pkey -in dhserver.key -text -noout

# Outputs:

# DH Private-Key: (2048 bit)

# private-key:

# 54:b1:7a:fc:e0:3e:06:15:92:b1:81:f2:47:54:0f:

# ...

# public-key:

# 00:b8:e9:ff:59:ba:8d:48:49:b5:00:99:d0:cc:a4:

# ...

# P:

# 00:dd:cf:3f:e8:43:db:cf:79:33:7d:27:4d:99:d3:

# ...

# G: 2 (0x2)

# generate signature

# This function extracts the hex block between two lines from the above parameters

function extract_hex_from_params_between_lines {

openssl pkey -in dhserver.key -text -noout | sed -n "/$1/,/$2/p" | tail -n +2 | sed -e '$ d' | tr -d ':\n '

}

DATA_DH_P=$(extract_hex_from_params_between_lines "P:" "G:")

DATA_DH_YS=$(extract_hex_from_params_between_lines "public-key:" "P:")

DATA_DH_G=2 # Copy this from the params yourself :)

# note: we will use this in the client too when verifying

# all the data here is public!

DATA_TO_HASH_HEX="${FULL_CLIENT_RANDOM}${FULL_SERVER_RANDOM}$(format_variable_size_hex_str $DATA_DH_P)$(num_to_hex $DATA_DH_G 1)$(format_variable_size_hex_str $DATA_DH_YS)"

hex_to_bytes $DATA_TO_HASH_HEX | openssl dgst -sha256 -sign server.key -out keyexchange.sign

# simulate send of parameters and public key to the server

# as done in `params` below

cp dhparam.pem ../client

cp dhserver.pem ../client

cp keyexchange.sign ../client

# Server to Client

msg_type: ServerKeyExchange

length: <message length>

body:

params:

dh_p: <prime number value from dhparam.pem in lab>

dh_g: <generator value from dhparam.pem in lab, probably 2>

dh_Ys: <public key from dhserver.pem in lab>

signed_params:

algorithm:

hash: 4 # sha256

signature: 1 # rsa

signature: RSA_SIGN(SHA256(client_random+server_random+params))

Aside:

What is the difference between the cipher suites with DH and DHE?

DH is (implicit) Diffie Hellman, and DHE is Diffie Hellman Ephemeral. The difference is that in DH, the public key of the server itself is a Diffie Hellman public key, that is then signed by the CA. This means that if you use DH, then every time the same keypair is used by the client, the shared secret will be the same. On the other hand, in DHE, the server’s public key is an RSA key and has nothing to do with the Diffie Hellman params. In practice, the Diffie Hellman parameters (Prime and Generator, dh_p and dh_g above) are generated in advance and given to the server (and is often not rotated at all!), and the server generates transient key-pairs on the server side (the private key and dh_Ys above), which is then sent over while negotiation.

Security wise, DH does not offer forward secrecy, while DHE does. Please see the Side Quest after this section to learn more!

5. Server Hello Done

The server says it’s done with its turn.

# Server to Client

msg_type: ServerHelloDone

length: <message length>

6. Client Verifies Certificate

The client checks the certificate to see that it matches the domain the URL is coming from, that it is currently valid, and that it is signed by a CA that it trusts.

# Lab, Client

cd client

# get the CA certificate

cp ../ca/cacert.pem ./

# verify that the cert is trusted by the ca

openssl verify -verbose -CAfile cacert.pem cert.pem

# verify that the name matches the SAN on the cert (manually)

openssl x509 -text -noout -in cert.pem

# extract the public key from the certificate

openssl x509 -pubkey -in cert.pem -noout > server.pem

# verify the signed key exchange message

# this proves that it is indeed the server that is sending the data,

# not some man in the middle

# note that $DATA_TO_HASH_HEX is being reused from the server

# this is ok, since we can recreate it using the data sent by the server

# I am leaving that out here for succinctness

hex_to_bytes $DATA_TO_HASH_HEX | openssl dgst -sha256 -verify server.pem -signature keyexchange.sign

7. Client Computes Master secret

Since the client now trusts the server, it goes ahead and derives the master secret. For this, it generates its own DH keys, and uses the prime and generator values supplied by the server to negotiate a shared secret (the DH pre-master secret). Note that to do this, you need access to all the public data which the server shared, but also the private key on the client. This is what keeps the secret… secret!

Explaining how the master secret is derived from the pre-master secret (the value negotiated with DH) is a bit too involved to be added here, but it is pretty simple math, described succinctly in the TLS RFC in the Computing the Master Secret section, with the PRF defined in Section 5

# Lab, Client

cd client

# client has received dhparam.pem above

# generate the client private

openssl genpkey -paramfile dhparam.pem -out dhclient.key

# and public

openssl pkey -in dhclient.key -pubout -out dhclient.pem

# take a look

openssl pkey -in dhclient.key -text -noout

# Generate shared secret (pre-master secret)

openssl pkeyutl -derive -inkey dhclient.key -peerkey dhserver.pem -out pre_master.bin

# Derive master secret from pre-master secret

PRF_SECRET_HEX=$(bytes_file_to_hex pre_master.bin)

PRF_SEED_HEX="$(str_to_hex 'master secret')${FULL_CLIENT_RANDOM}${FULL_SERVER_RANDOM}"

openssl pkeyutl -kdf TLS1-PRF -kdflen 48 -pkeyopt md:SHA256 -pkeyopt "hexsecret:$PRF_SECRET_HEX" -pkeyopt "hexseed:$PRF_SEED_HEX" -out master_secret.bin

# View the master secret

xxd master_secret.bin

Aside:

Why do we not simply use the secret derived from DH (what is called the “pre-master secret” above) as the master secret?

This is to abstract away the key exchange part of TLS from the encryption part of TLS.

The idea is that the output of the key exchange step is always 48 bytes of data that is guaranteed to be the same shared secret between client and server. This way, the key exchange method itself can pass any data to the “pre-master to master secret conversion” step, and the output is standardized to the encryption step. The master secret derivation acts as the “API” between these steps.

8. Client Key Exchange Message

The client proceeds to send back the information about its public DH parameter to the server.

msg_type: ClientKeyExchange

length: <message_length>

body:

exchange_keys:

dh_public: <public key from dhclient.pem>

# Lab, Client

cd client

cp dhclient.pem ../server

9. Client Change Cipher Spec

The client now sends a ChangeCipherSpec message, which is a single byte message which just says that everything beyond this will use the negotiated cipher.

This is technically an entirely different type of message than a TLS Handshake message (ie, it does not fit in the Handshake struct and does not have an entry in HandshakeType), even though it is conceptually part of the “TLS Handshake.”

This is because of how TLS transmits data.

SSL sends messages that are encoded over records. Several messages of the same type can be sent in the same record. For example, several Handshake messages can be sent in the same record. However, a ChangeCipherSpec message modifies the way the following messages are encoded! So, TLS forces a ChangeCipherSpec message into its own single-message record to prevent confusion over where the changed cipher spec takes effect from.

10. Client Finished

Finally (for the client), the client sends a Finished message.

Note that this will now be encrypted with AES, as we have negotiated!

The handshake_messages used in the verify_data is a concatenation of all the handshake messages received so far. The exact implementation isn’t super important here, just know that the server can also construct this and verify that the data is correct.

msg_type: Finished

length: <message length>

body:

verify_data: PRF(master_secret, "client finished", Hash(handshake_messages))

11. Server Computes Master secret

The server, having now received the public DH parameters of the client, has everything it needs to compute the shared secret itself. Note that we’re using the private secret of the server, and the public parameter of the client!

# Lab, Server

cd server

# Generate shared secret (pre-master secret)

# note that we are using the server secret and the client public now

# this should be the same as the client!

openssl pkeyutl -derive -inkey dhserver.key -peerkey dhclient.pem -out pre_master.bin

# Derive master secret from pre-master secret

# Since the pre-master secret will be the same for the client and server,

# and all the other inputs below are also the same,

# the resulting master will be the same as well

PRF_SECRET_HEX=$(bytes_file_to_hex pre_master.bin)

PRF_SEED_HEX="$(str_to_hex 'master secret')${FULL_CLIENT_RANDOM}${FULL_SERVER_RANDOM}"

openssl pkeyutl -kdf TLS1-PRF -kdflen 48 -pkeyopt md:SHA256 -pkeyopt "hexsecret:$PRF_SECRET_HEX" -pkeyopt "hexseed:$PRF_SEED_HEX" -out master_secret.bin

# View the master secret

# this should be the same as the client!

xxd master_secret.bin

12. Server Change Cipher Spec and Finished

Similar to the client ChangeCipherSpec and Finished, the server also sends the same data.

Note that the label in verify_data has changed.

msg_type: Finished

length: <message length>

body:

verify_data: PRF(master_secret, "server finished", Hash(handshake_messages))

And voila, you have a TCP connection encrypted with AES 256!

Side Quest: Why not just use RSA Key Exchange?

Let me define terms here first:

The goal of the Key Exchange step in TLS is to get a master secret in a standardized format. The idea is that this standardized master secret can be used as the seeding secret in whatever encryption algorithm we use later, no matter what you use to arrive at the master secret. You will usually hear Diffie Hellman (or an Elliptic Curve variant) being used for this.

RSA is generally used as a signature in TLS - to prove that the data you’re sending does indeed come from you. However, you can also use RSA to send a client generated secret to the server (a “pre-master key”), using which you can derive a master secret. This is the RSA Key Exchange. Remember, data can only be encrypted from the client to the server before the encrypted tunnel is set up, and the key exchange is needed to set up that tunnel!

At first, this looks really nice! It doesn’t require any overhead in computing Diffie Hellman secrets, so it is more performant and efficient. However, its drawback is that it doesn’t offer Perfect Forward Secrecy. Very mysterious name, but a very simple concept:

Imagine I am a hacker that’s trying to get your server data. I am working very hard to break into your server. I know this will take some time, so I record all the data that is going to your server in the mean time. They are all protected by TLS, so they are useless to me right now. One day, I finally get access to your server. I steal your private keys and get ready to pwn you. But you are smart, so you detect me, you kick me out, and you immediately replace all your private keys and certificates. Aw man, all that work, all for nothing!

Or is it? I notice that you are using the RSA key exchange mode. This means that the secret that’s used for encryption comes only from the client generated secret. I can now decrypt this on all of the TLS data that I was storing in the past, and read all the TLS-protected data I had stored earlier that I could not read before! If you had been using Diffie Hellman, this is not possible, since DH does not rely on a single secret to generate the master secret, it relies on math done between two different values, which could even be public! I’m not getting into how this works, but there are excellent explanations of DH elsewhere. For example, this video on Diffie Hellman on Khan Academy Labs

The TLS (1.3) Handshake

The TLS 1.3 Handshake is shorter and simpler than 1.2, basically combining several steps of TLS 1.2 together, amongst other changes. We won’t explore this much here, but you should be armed with the knowledge to understand it, if you must.

Sending data over TLS

Generating AES Key from Master Secret

We skipped a little step in the TLS Handshake, which is where the master secret is expanded into the keys needed for encryption and MAC. This is done using the same PRF function we used for deriving the master secret from the pre-master secret earlier, except we generate enough data for all our keys.

# Lab, Client and Server

cd server

# Key Expansion

PRF_SECRET_HEX=$(bytes_file_to_hex master_secret.bin)

PRF_SEED_HEX="$(str_to_hex 'key expansion')${FULL_CLIENT_RANDOM}${FULL_SERVER_RANDOM}"

openssl pkeyutl -kdf TLS1-PRF -kdflen 128 -pkeyopt md:SHA256 -pkeyopt "hexsecret:$PRF_SECRET_HEX" -pkeyopt "hexseed:$PRF_SEED_HEX" -out keys_expanded.bin

# Break the expanded keys into the required keys for AES_256_CBC_SHA_256 mode:

bytes_file_block_to_hex keys_expanded.bin 0 32 > client_write_MAC_key.bin

bytes_file_block_to_hex keys_expanded.bin 32 32 > server_write_MAC_key.bin

bytes_file_block_to_hex keys_expanded.bin 64 32 > client_write_key.bin

bytes_file_block_to_hex keys_expanded.bin 96 32 > server_write_key.bin

Message From Server To Client

Let’s say the server wants to send a client a plaintext message: HELLO WORLD. TLS itself does not care about the application layer protocol, and treats this text as simply a bunch of bytes.

Each message is sent as arbitrary length records, which is further split into fragments. In our case, HELLO WORLD fits into one fragment:

# TLSPlaintext

type: 23 # application_data

version: { major: 3, minor: 3 }

length: 12

fragment: HELLO WORLD

We skip compression, because we have elected to use NULL. The data will look exactly the same as above, although of type TLSCompressed.

We then encrypt the data. For this, we generate an IV, compute the HMAC, find the padding necessary to get the size of the message to a multiple of 16 (block size of AES256), and encrypt the data. We then send this data to the client.

# TLSCiphertext

type: 23 # application_data

version: { major: 3, minor: 3 }

length: <length of below fragment>

fragment:

IV: 454e1fe2d1880c85766c3626f2a3386b

data: AES256 of-

content: HELLO WORLD

MAC: d1bda6d0c3273b00fa531e8424ff0f171536194e936b0d623dba19570f5035e5 # HMAC(<server mac write key>, sequence_number + TLSCompressed.type + TLSCompressed.version + TLSCompressed.length + TLSCompressed.fragment)

padding: 0x05 0x05 0x05 0x05 # this is the padding_length, repeated enough times to make the block 16 bytes

padding_length: 0x05

# data_raw: b60fbfec7c9a3acdb820eeeb52279cc5c3f321c690c833d6e4c71eba3db8b77f14ba9464c90e3bb9b3dbdae2c2c7e499af10bd2de59aaae5a40261827c7d9605aff259867cc2f38f98dc941bf836482cb85909c48227158182bc9fa3a1e3a5b6

# Lab, Server

cd server

CONTENT="HELLO WORLD"

CONTENT_HEX=$(str_to_hex $CONTENT)

DATA_TYPE=$(num_to_hex 23 1) # Hex of 23

DATA_VERSION_MAJOR=$(num_to_hex 3 1)

DATA_VERSION_MINOR=$(num_to_hex 3 1)

# The format of this data is specified in the spec

# the first number is the sequence number, which is assumed to be 0. It is 64 bits/8 bytes

HMAC_DATA="$(num_to_hex 0 8)${DATA_TYPE}${DATA_VERSION_MAJOR}${DATA_VERSION_MINOR}${CONTENT_HEX}"

# Compute the HMAC

# we need to cut since the sha produces output with some unnecessary text

DATA_HMAC=$(hex_to_bytes "$HMAC_DATA" | openssl sha256 -mac HMAC -macopt "hexkey:$(cat server_write_MAC_key.bin)" -hex | cut -d ' ' -f 2)

# See the HMAC value

echo $DATA_HMAC

# Calculate Padding

# Divide HMAC data size by two as two hex characters form one byte of data

CONTENT_LENGTH=$(hexstrlen "${CONTENT_HEX}${DATA_HMAC}")

PADDING_LENGTH=$((16-( $CONTENT_LENGTH % 16 ) ))

PADDING_HEX=$(num_to_hex $PADDING_LENGTH 1)

PADDING=$(repeat_times $PADDING_HEX $PADDING_LENGTH)

# This is the data we need to encrypt

ENC_CONTENT="${CONTENT_HEX}${DATA_HMAC}${PADDING}"

# Generate the initialization vector for the CBC

IV=$(openssl rand -hex 16)

# Encrypt the data using the server write key

echo -n "$ENC_CONTENT" | openssl enc -aes-256-cbc -nosalt -e -K $(cat server_write_key.bin) -iv $IV -p -nopad -out request.enc

# Send request to client

cp request.enc ../client

On the other side, we decrypt this data and decode it using the known format. Since we know where the key comes from, and the IV is given in the message itself, you should be able to figure out how to do this! 😄️

That’s about it! Perhaps later, I can write notes about how this works with UDP and QUIC/HTTP3, but this article is long enough as-is.