To put it in standard interview format,

Given n machines with m ports each, how many TCP connections can be made theoretically from one to the other?

Thinking up an answer

The “simple logic”

For those familiar with the socket analogy, it’s easy to come up with a plausible answer.

m ports on each, you can make m “connections” (think connecting an electrical plug to a socket).

floor(mn/2) possible connections between n machines with m connections each.

Given some elementary knowledge of TCP, you would know that ports on a standard linux machine go from 1-65535, giving you m = 65535, and voila, you have an answer!

Hmm, what about servers, though?

You notice that the limiting factor in your connection count is that each socket can either make one connection or receive one connection, and that you have reached the highest possible answer in this paradigm. This is when you remember that a server can listen to multiple requests on a single TCP port!

You try to remember if this happened by opening a new connection for each new request, or if there’s something else ongoing. You seem to remember that each time a socket accepts a connection, a file descriptor is created. This isn’t a socket. You note down that you’ve gotta go read more about file descriptors later, but for now, time to tackle the original question!

m * (n-1) connections, just by making a connection from every port on every machine to one “server” machine. Is this it? No.

mn - 2. There can’t be more. Right?

Ok, but what’s the answer?

You’re pretty happy with your answer. But you want to be sure. Maybe it’s possible two more connections to get the full mn connections, and you’ve missed something minor. Those last two connections are the difference between someone who can think of good answers and someone who knows answers, you muse.

You hit up your favorite online Q&A site, and find the answer:

m^2 * n^2.

What?

How is that even possible?

The answer, in theory

If you go searching around at all, you will find the mantra of disambiguating a TCP connection:

A TCP connection is

identified by the 5-tuple of

(

protocol,

source ip,

source port,

destination ip,

destination port

)

Taking this as gospel, it is clear how we get to the m^2*n^2 figure: we just multiply through by each of the 4 variable parts in turn (protocol is assumed to be fixed to TCP).

This is, to me, both highly intuitive as well as kind of weird.

It is intuitive as that’s how connections are tracked anywhere we deal with TCP. It’s how TCP connections are thought of when setting up iptables rules; it’s how TCP connections are thought of during tcpdump; it’s how TCP connections are set up when binding them to sockets.

It’s kind of weird because we never think of TCP this way when writing apps. When we write a server-client application, we almost always assume the clients socket belongs exclusively to the server. This is something lost in the abstraction between L4 and L7, and possibly rightfully so! The client handles the port sharing on its end, and that’s something we don’t have to care about on the server, so why think about it at all?

Given you may never have seen this in the wild though, you may ask:

But is that even actually possible?

PS: Please go to this repo for instructions on how to run this yourself. Things feel a lot more real if you actually run these yourself!

As a matter of fact, yes it is!

To prove that this is possible, we need to show that if we change any of the four parameters in (source ip, source port, destination ip, destination port), we can create a new connection. Out of these, a few are trivial:

- If you change

source ip, it’s equivalent to connecting from a different machine, so there’s not much to test out there. - If you change

source port, it’s equivalent to a “new connection” on the same machine, so there’s nothing to test out there either.

These are situations where different clients connect to the same server.

What we are left to prove is:

- Given a fixed

(source ip, source port, destination ip), we can connect to multipledestination ports. - Given a fixed

(source ip, source port, destination port), we can connect to multipledestination ips.

These are situations where the same “socket” (ie source ip, source port pair) make a connection to two different servers. In a way, it’s the opposite of how a server accepts connections from multiple clients.

Test Setup

We have a server and a client

Importantly, the client creates a socket with the SO_REUSEADDR option set. This allows multiple clients to connect to the same (source ip, source port) combo.

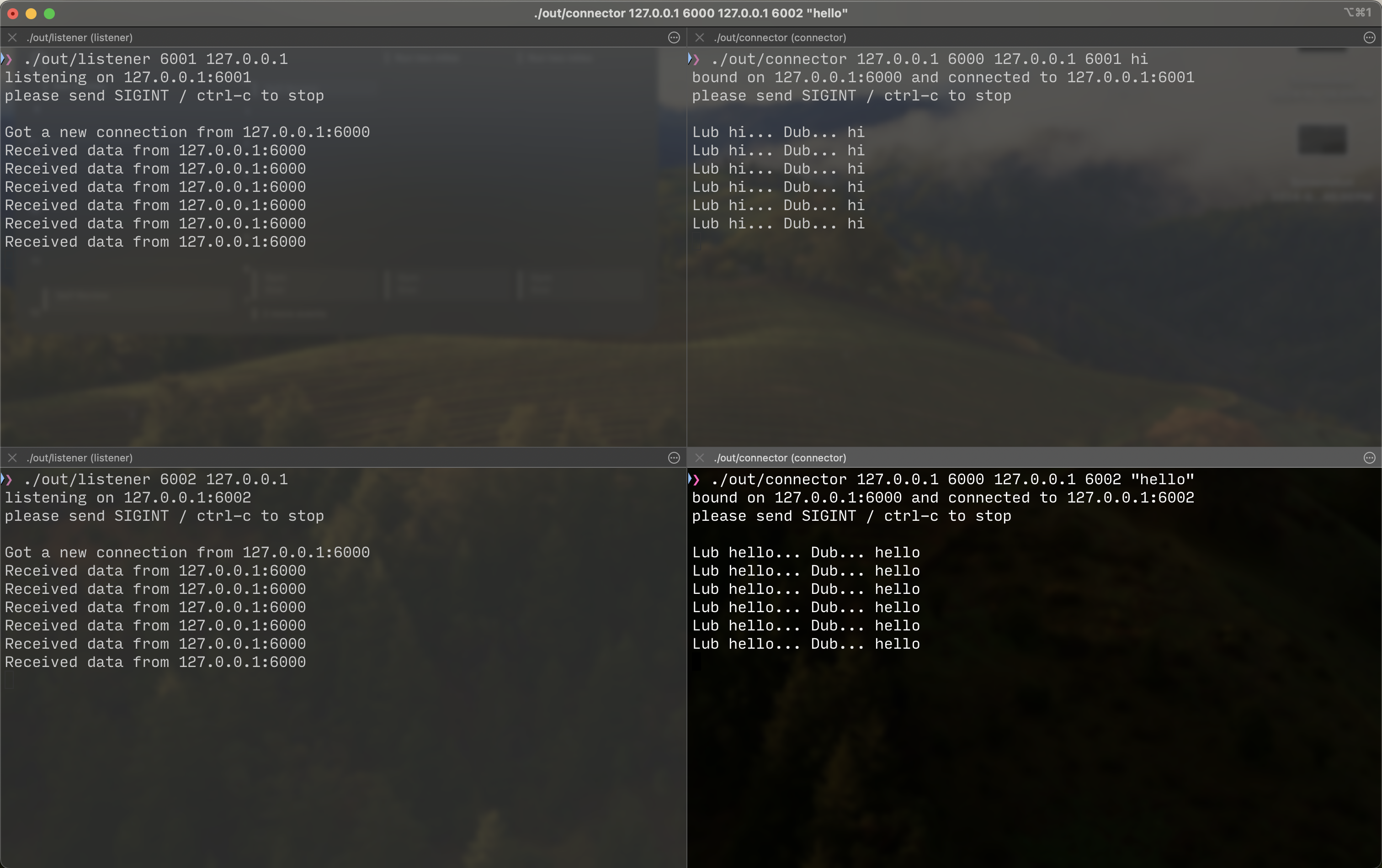

Testing for multiple destination ports

We spin up two listeners on two different ports (6001 and 6002), and spin up two connectors on the same port (6000), fixing all ips on loopback.

Success! Both the servers are getting requests from

Success! Both the servers are getting requests from 127.0.0.1:6000, but they have different data being echoed back!

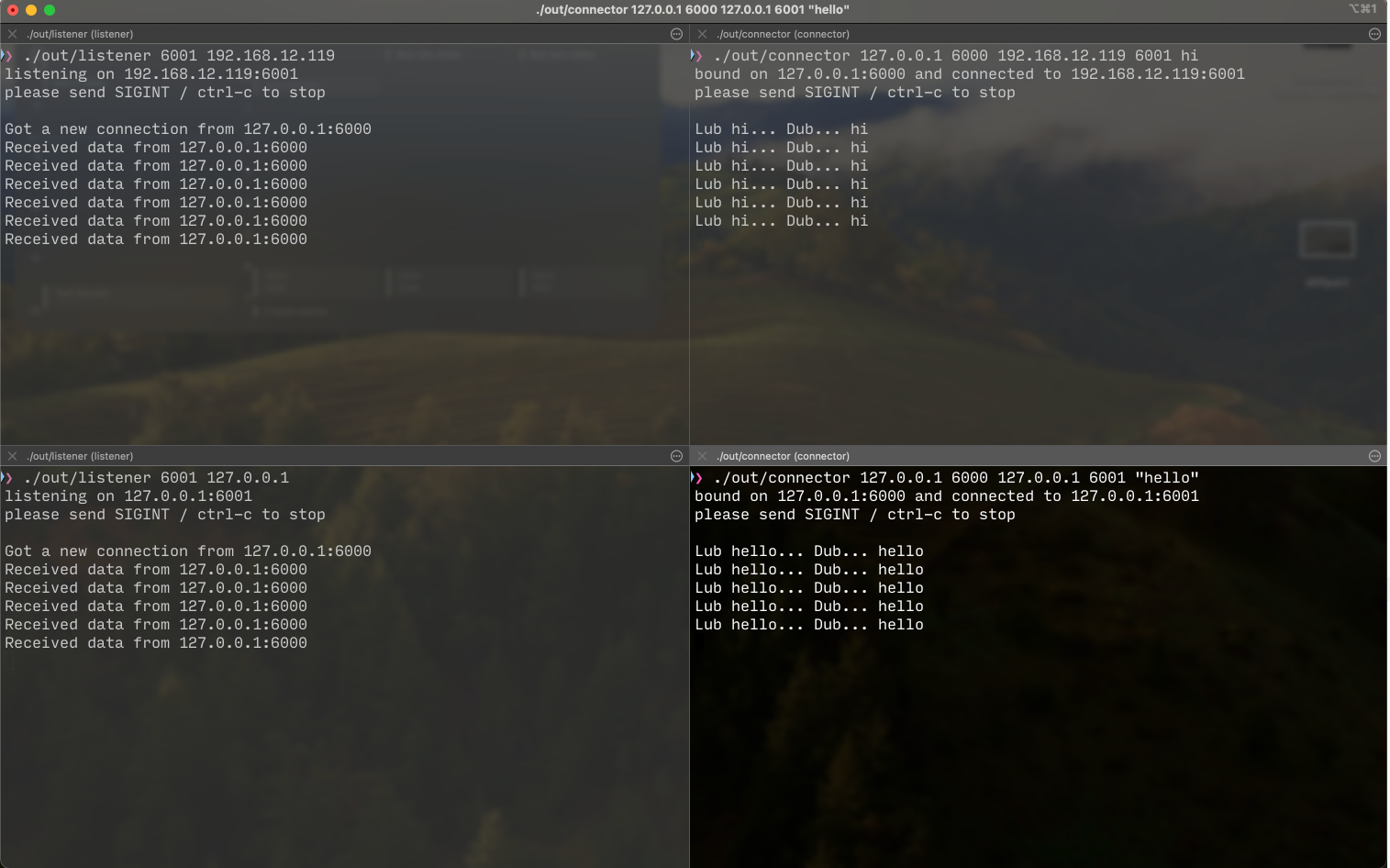

Testing for multiple destination ips

We spin up two listeners on two different ips (loopback and local lan ip) but the same port, and spin two connectors on the same port (6000).

Success! Both the servers are getting requests from

Success! Both the servers are getting requests from 127.0.0.1:6000, but they have different data being echoed back again!

You may want to play around with interesting cases yourself! Some suggested experiments are included in the README over on Github.

Practical Considerations

Let’s punch in some numbers.

n = ip space ~ 2 ^ 32

m ~ 2 ^ 16

total number of connections = ( 2 ^ 32 * 2^16 ) ^ 2 = 2^96 ~ 8*10^28

ie, possible total number of connections = 80 billion billion billion

Of course, that’s not practically possible. You will run into other limitations far before you reach anything close to that number.

Some of them are:

- The number of connections your CPU can handle, especially given TLS today

- The number of file descriptors that can be open at a time (

ulimit) - The number of file descriptions that you can store in memory

- The time needed to open that many connections 🤣

However, this is more meant to be a theoretical explanation, so let’s leave it at that!